Access to communications data by the intelligence and security Agencies

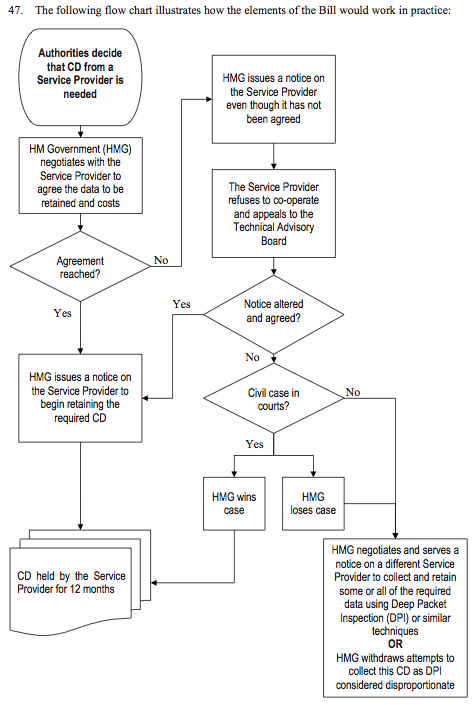

Have a look at this flow chart. It’s taken from the Intelligence and Security Committee’s report on the Communications Bill, and “illustrates how the elements of the Bill would work in practice.” It is UK democracy at work.

It starts with the authorities deciding that certain data is wanted. If the service provider objects, see how he has the right to appeal. If he accepts the request, he gets a notice to retain the required data. If he rejects the request, he gets a notice to retain the required data. If he still objects, it might go to court. If he wins the case, “HMG negotiates and serves a notice on a different Service Provider to collect and retain some or all of the required data using Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) or similar techniques.” In other words, they chose a different ISP and start all over again. That’s pure democracy: keep asking the question until you get the answer you want.

Of course, it’s not the only worrying thing about the Access to communications data by the intelligence and security Agencies report. My primary concern is that it is not an investigation into the Communications Bill at all. It is really a libation to the Bill. Its only criticism is that the government should have done a better job at selling the Bill to the population. But having said that, the Committee still tries to obfuscate and mislead.

Consider the section on ‘encryption’. It is heavily redacted (another example of modern democracy: ‘don’t tell the plebs what we’re doing’). It effectively says little more than

From the encryption section of the report

Makes you wonder, doesn’t it. What are those ‘options’? And what does it mean for the service provider to provide an unencrypted version of encrypted communications data?

I asked two interested experts to explain the issue for me – and rather than try to comment on their replies, I’m reproducing them in full.

James Firth, CEO of the Open Digital Policy Organisation Ltd

The problem arises because communications can be – effectively – layered. So a portion of ‘content’ at one (higher) layer is actually communications data at a lower layer.

A classic example is webmail. Alice logs in to mail service provider G via secure HTTPS and sends a message to Bob. All her ISP knows is that Alice has a web session with G.

Various proposals being touted – sometimes in the various drafts – include forcing mail service providers to abide by the Comms Bill. Jurisdiction could be enforced in some way for any company with a UK presence, but it would be impractical as the Bad Guys would just use other companies.

But there have been scarier options touted.

If Alice didn’t use a secure method to connect to her mail service provider her ISP could be forced to scan all CONTENT in order to detect nested communications data. In this model her ISP would scrape the email “to” and “from” fields from her web session. I doubt this would pass muster with various EU Directives but that’s been suggested.

Even scarier suggestion – if Alice DID use SSL to connect to her mail service provider it has been suggested – I have a very good contact confirming this – that legislation could be introduced to force her ISP to store the whole encrypted transaction, even though this includes the content.

The idea being that HMG could get a court order – here or in e.g. the US – at a later date to force her mail service provider to disclose their private SSL key. From that it would – in *some cases* – be possible to replay the SSL transaction to discover the session key and decrypt the contents, then extract the communications data, and – honest guv – ignore any content.

The major flaw in this plan is that Google, as one mail service provider, has rolled-out a feature called forward secrecy (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perfect_forward_secrecy).

Forward secrecy introduces, essentially, a second negotiated secret into the SSL transaction; a secret known only by the client web browser. The protracted SSL handshake with forward secrecy ensures that if one private key was later compromised – e.g. the mail service provider’s key – an attacker would still not be able to reproduce the plaintext from a captured encrypted session.

Clever mail service providers would never want to be in a position where they are forced by a court to hand over their private keys, so forward secrecy is actually in their interests as it devalues their private key as it won’t alone decrypt a captured session. In fact the second secret needed to decrypt a session with perfect forward secrecy should have been destroyed by the client and the server as soon as the session ends.

Alexander Hanff, managing director at Think Privacy Ltd

When an SSL connection is made a ‘tunnel’ is set up and as a result all of the HTTP headers are encrypted (these include the specific web page you are requesting from the server) but the TCP and IP data is not encrypted as they exist on different OSI layers – HTTP/SSL exist in layers 5-7 whereas TCP is layer 4 and IP is layer 3 (if my memory serves me correctly you might want to double-check that).

As you correctly state, it would be impossible to get the encrypted content to the server if the 3rd and 4th OSI layers were encrypted, so yes there is still a DNS lookup (which means the ISP knows the domain and the IP address you are trying to communicate with) but they would not know which web page you are trying to access within that domain.

The same should be true of emails which are not hosted by the ISP (for example I run my own email servers) they would know which email server I am trying to communicate with but since my emails are transported over SSL/TLS the would not know whom I am communicating with or anything else which is held within the encrypted packets (I run my own email servers to circumvent the Data Retention aspects of RIPA/Data Retention Directive).

That said, the ISP could easily set up Man in the Middle attacks similar to how Phorm did with their DPI boxes which would allow them to decrypt everything (including the content) which is what I presume was the redacted content in the report released yesterday when they were talking about the government has a feasible method of dealing with encryption. This of course would be completely illegal under RIPA (without a warrant) so they would need to introduce legislation to do this (which would put them in breach of the EU Data Retention Directive but as we know the UK gov are not good at complying with EU Directives so they probably wouldn’t care).

So in summary, yes encryption restricts them from obtaining some of the higher level data they want but not the low-level data such as domain and IP.

Notice that there is one common element in these two replies: further legislation. It seems highly likely, then, that this Communications Bill will be supplemented by altogether more intrusive legislation (the ‘options’) when the authorities finally realise what everyone has been telling them: this Communications Bill isn’t what they say and will not work. And that, of course, is democracy at work: keep asking the question until you get the response you want.